Every day scientists publish research results. Most often the resulting technical papers are sent to the scientific journals and often the abstracts of these papers make their way onto the Internet as a stream of news items that one can subscribe to through RSS feeds[1]. A major source of high quality streamed science data is the Cornell University Library ArXiv.org which is a collection of over one million open-access documents. Other sources include the Public Library of Science (PLOS ONE), Science and Nature. In addition when science reporters from the commercial press hear about new advances, they often publish articles about these discoveries that that also appear as part of the RSS stream. For example Science Daily, Scientific American, New Scientist, Science Magazine and the New York Times all have science news feeds.

Suppose you are doing research on some topic like “black holes and quantum gravity” or “the impact of DNA mutation on evolution” or “the geometry of algebraic surfaces”. Today you can subscribe to some of these topics through the RSS feed system, but suppose you had a virtual assistant that can alert you daily to any newly published progress or news reports related to your specific scientific interests. You may also want to see science results from disciplines that are different from your standard science domains that are may be related to your interests. What I would really like is a “Science Cortana” that can alert me with messages like “here are some interesting results from mathematics have been published today that relate to your science problem…” or “Yo! You know the problem you have been working on … well these people have solved it.”

Object classification using machine learning is a big topic these days. Using the massive on-line data collection provided by user photos in the cloud and movies in YouTube, the folks at Google, Microsoft, Facebook and others have done some amazing work in scene recognition using deep neural networks and other advanced techniques. These systems can recognize dogs down to the breed … “this dog is a Dalmatian” … or street scenes with descriptions like “a man with a hat standing next to a fire truck”. Given this progress, it should be an easy task to use conventional tools to be able to classify scientific paper abstracts down to the scientific sub-discipline level. For example, determine if a paper is about cellular biology or genomics or bio-molecular chemistry and then file it away under that heading. In this post I describe some experience with building such an application.

This is really the first of a two-part article dealing with cloud microservices and scientific document analysis. The work began as I was trying to understand how to build a distributed microservice platform for processing events from Internet sources like twitter, on-line instruments, and RSS feeds. Stream analytics is another very big topic and I am not attempting to address all the related and significant issues such as consistency and event-time correlation (see a recent blog post by Tyler Akidau that covers some interesting ideas not addressed here.) There are many excellent tools for stream analytics (such as Spark Streaming and Amazon Kinesis and Azure Stream Analytics) and I am not proposing a serious alternative here. This and the following post really only address the problem of how can a microservice architecture be used for this task.

The application: classifying scientific documents by research discipline

It turns out that classifying scientific documents down to the level of academic sub-discipline is harder than it looks. There are some interesting reasons that this is the case. First, science has become remarkably interdisciplinary with new sub-disciplines appearing every few years while other topics become less active as the remaining unsolved scientific problems become scarce and hard. Second a good paper may actually span several sub-disciplines such as cellular biology and genomics. Furthermore articles in the popular press are written to avoid the deeply technical science language that can help classify them. For example, a story about the search for life on the moons of Jupiter may be astrophysics, evolution, geophysics or robotics. Or all of the above. If the language is vague it may not be possible to tell. Finally there is the issue of the size of the available data collections. There are about 200 science articles published each day. As an event stream this is clearly not an avalanche. The work here is based on a harvest of several months of the science feeds so it consists of about 10,000 abstracts. This is NOT big data. It is tiny data.

To approach the machine learning part of this problem we need two starting points.

- A list of disciplines and subtopics/sub-disciplines we will use as classification targets

- A training set. That is a set of documents that have already been classified and labeled.

For reasons described below the major disciplines and specific sub-disciplines are

Physics

Astrophysics and astronomy

General Relativity, Gravitation, Quantum Gravity

Condensed Matter Physics

High Energy Physics

Mathematical Physics

Nuclear Physics

Quantum Physics |

Biology

Neuroscience

Cell Behavior

Genomics

Evolution

Subcellular Organization

Tissue/Organs

Modeling |

Computer Science

Artificial Intelligence & Machine Learning

Engineering & Math Software

CS and Game Theory

Data Structures, Algorithms & Theory

Systems, Programming Languages, Soft Eng

HCI & Graphics

Databases & Information Retrieval

Networks, Security and Soc Nets |

Finance

Computational Finance

Economics

Statistical Finance

Portfolio Management

Markets

Risk Management

General Finance |

Math

Algebra

Topology

Analysis

Other |

|

Table 1. Semi-ArXiv based topic and sub-discipline categories. (ArXiv has even finer gained categories that are aggregated here.)

Unfortunately, for the many of our documents we have no discipline or subtopic labels, so they cannot be used for training. However the ArXiv[2] collection is curated by both authors and topic experts, so each document has a label. Consequently we have built our training algorithms to correspond to the discipline subtopics in ArXiv. In some cases the number of discipline subtopics in ArXiv was so large it was impossible for our learning algorithm to distinguish between them. For example mathematics has 31 subtopics and computer science has 40. Unfortunately the size of the data sample in some subtopics was so tiny (less than a few dozen papers) that training was impossible. I decided to aggregate some related subtopics for the classification. (For mathematics I chose the four general areas that I had to pass as part of my Ph.D. qualification exam! A similar aggregation was used for computer science.)

ArXiv has another discipline category not represented here: Statistics. Unfortunately, the interdisciplinary problem was so strong here that most of Statistics looked like something else. A large fraction of the statistics articles were in the category of machine learning, so I moved them to the large sub-discipline of CS called AI-ML. The rest of statistics fell into the categories that looked like applied math and theory so they were moved there.

Using the ArXiv classification as training data worked out well but there was one major shortcoming. They do not have all major science disciplines covered. For example there is no geoscience, ecology or psychology. (PLOS covers a much broader list of disciplines and we will use it to update this study soon.) This lack of earth sciences became very noticeable when classifying papers from the popular science. I will return to this problem later.

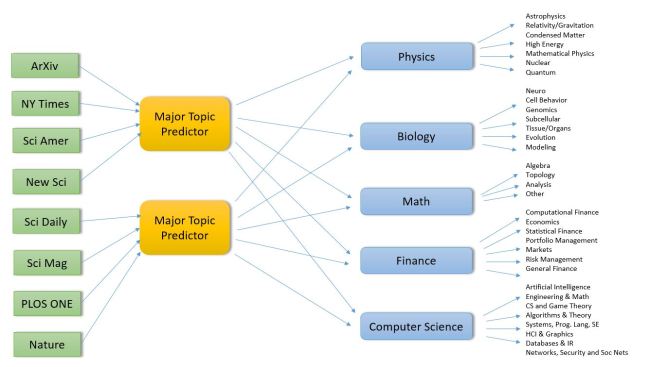

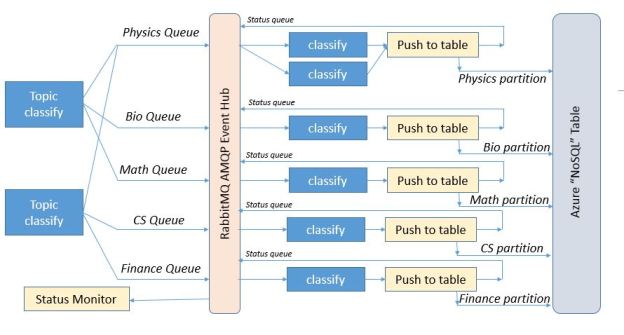

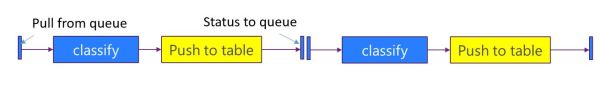

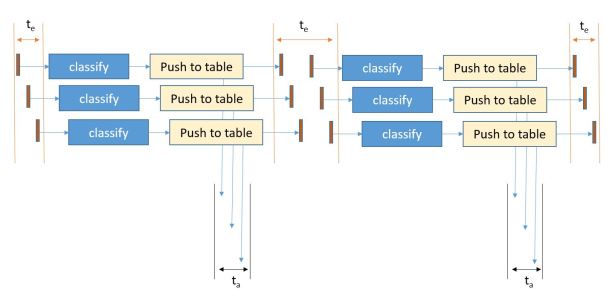

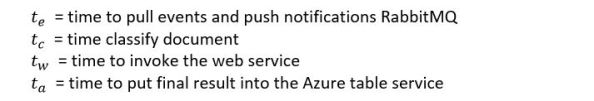

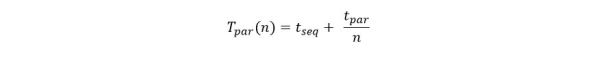

The application is designed as three layers of microservices as shown in the diagram below (Figure 1). The first layer pulls recent docs from the RSS feeds and predicts which major category is the best fit for the document. It then pushes this document record to second level services specific to that topic. In fact, if our classifier cannot agree on a single topic, it will pick the best two and send he document to both subtopic analyzers. The second level service predicts which subtopics are the best fit and then pushes the document to a storage service where it is appended to the appropriate sub-discipline

[1] Technically RSS is not a “push” event technology. It needs another service to poll the sources and push the recent updates out as events. That is what we do here.

[2] FYI: ArXiv is pronounced archive. Very clever.

Figure 1. Basic Microservice architecture for science document classifier (click to enlarge)

The output will be a webpage for each subtopic listing the most recent results in that sub-domain.

What follows is a rather long and detailed discussion of how one can use open source machine learning tools in Python to address this problem. If you are not interested in these details but you may want to jump to the conclusions then go to the end of the post and read about the fun with non-labeled documents from the press and the concluding thoughts. I will return to the details of the microservice architecture in the next post.

Building the Document Classifiers

The document analyzer is a simple adaptation of some standard text classifiers using a “Bag of Words” approach. We build a list of all words in the ArXiv RSS feeds that we have harvested in the last few months. This collection is about 7100 ArXiv documents. The feed documents consist of a title, author list, abstract and URL for the full paper. The ArXiv topic label is appended to the title string. Our training is done using only the abstract of the article and the topic label is used to grade the prediction.

The major topic predictor and the sub-discipline classifiers both use the same code base using standard Python libraries. In fact we use five different methods in all. It is common believe that the best classifier is either a deep neural net or the Random Forest method. We will look at deep neural nets in another post, but here we focus on Random Forest. This method works by fitting a large number of random binary decision trees to the training data. Another interesting classifier in the Scikit-Learn Python library is the Gradient Tree Boosting algorithm. This method uses a bunch of fixed size trees (considered weak learners) but then applies a gradient boosting to improve their accuracy. In both cases it is the behavior of the ensemble of trees that is used for the classification.

For any Bag-of-words method you first must convert the words in the training set into a dictionary of sorts so that each document is a sparse vector in a vector space whose dimension is equal to the number of words in the dictionary. In this case we use a “count vectorizer” that produces a matrix of word token counts. We then apply a Term Frequency – Inverse Document Frequency (TFIDF) normalization to a sparse matrix of occurrence counts. This is a sparse matrix where each row is a unit vector corresponding to one of the training set documents. The size of the row vector (the number of columns) is the size of the vocabulary. The norm of the row vector is 1.0. In the code, shown below, we then create the random forest classifier and the gradient tree boosting classifier and train each with the training data.

Figure 2. Sample Python code for building the random forest and gradient tree boosting classifiers.

Finally we make a prediction for the entire set of documents in the ArXiv collection (all_docs in the code above). This is all pretty standard stuff.

The training set was a randomly selected subset of ArXiv data. Using a relatively small training set of no more than 400 of the documents from each category we got the following results. With five major categories that represents about 33% of all of the ArXiv documents. This provided a correct classification for 80% of the data using only the Random Forest Classifier. Unfortunately the distribution of documents among the various categories is not uniform. Physics and Math together constitute over half of the 5500 documents. Using a larger training set (75% of the documents from each category) gave a stronger result. However, when we use both Random Forest (RF) and Gradient Boosting (GB) and consider the result correct if either one gets the answer right, we get a success rate 93%. Looking more closely at the numbers, the success rate by topic is shown below. We have also listed the relative false positive rate (100*number of incorrect predictions/the total size of the category)

| Major topic |

% RF or GB correct |

% relative false positive rate |

| Physics |

97.5 |

3.2 |

| Math |

92.3 |

14.6 |

| Bio |

88.9 |

1.6 |

| Compsci |

86.8 |

9.7 |

| Finance |

90.8 |

2.8 |

Table 2. Basic top-level classifier results with success percentage if one of the two methods are correct. The relative false positive rate is

100*total incorrect predictions of a document belonging to domain-x/sizeof(domain-x)

It is also worth noting that RF and GB agree only about 80% of the time and RF is only slightly more accurate than GB. The false positive rates tell another story. For some reason Mathematics is over predicted as a topic. But there are additional more sociological factors at work here.

The choice of the ArXiv label often reflects a decision by the author and tacit agreement by the expert committee. For example the article titled

“Randomized migration processes between two epidemic centers.”

Is labeled in ArXiv as [q-bio.PE] which means quantitative biology, with the sub area “population and evolution”. This paper is illustrates one of the challenges of this document classification problem. Science has become extremely multidisciplinary and this paper is an excellent example. They authors are professors in a school of engineering and a department of mathematics. If you look at the paper it appears to be more applied math then quantitative biology. This is not a criticism of the paper or the ArXiv evaluators. In fact this paper is an excellent example of something a quantitative biologist may wish to see. The Random Forest classifier correctly identified this as a biology paper, but the gradient boosting method said it was math. Our best of three (describe below) method concluded it was either computer science or math. (In addition to some rather sophisticated mathematics the paper contains algorithms and numerical results that are very computer science-like.)

All of this raises a question. Given a science article abstract, is there a single “correct” topic prediction? Textbooks about machine learning use examples like recognizing handwritten numerals or recognizing types of irises where there is a definitive correct answer. In our case the best we can do is to say “this document is similar to these others and most of them are in this category, but some are in this other category”. Given that science is interdisciplinary (and becoming more so) that answer is fine. The paper should go in both.

This point can be further illustrated by looking at the subtopic level where the distinction between sub-disciplines is even more subtle. Physics is the most prolific science discipline in the ArXiv. It has many sub-discipline topics. For our purpose we have selected set listed in Table 1. Our classifier produced the following results when restricted to Physics using a training set consisting of 75% of the items in each category but no more than 200 from each. The overall score (either RF or GB correct) was 86%, but there were huge false positives rates for General Relativity (GR-QG) and High Energy Physics (HEP) where we restricted HEP to theoretical high energy physics (HEP-th).

| Sub-discipline |

%correct |

100*relative false positive rate |

| Astrophysics |

88.5 |

6.24 |

| General Relativity & Quantum Grav |

89.4 |

28.33 |

| Condensed Matter |

74.7 |

0.0 |

| High Energy Physics |

77.8 |

21.4 |

| Mathematical Physics |

73.7 |

0.0 |

| Nuclear Physics |

66.7 |

0.0 |

| Quantum |

74.6 |

0.0 |

Table 3. Classifier results for Physics based on RF or GB predicting the correct answer

In other words the system predicted General Relativity in places were that was not the correct category and High energy physics also incorrectly in others. These two subtopics tended to over-predict. A closer look at the details showed many HEP papers were labeled as GR-QG and visa-versa. There is a great way to see why. Below are the “word cloud” diagrams for HEP, GR-QC and Astrophysics. These diagrams show the relative frequency of words in the document collection by the size of the font. Big words are “important” and little ones less so. As you can see, the HEP and GR-QC word clouds are nearly identical and both are very distinct from Astrophysics.

Figure 3. Word cloud for documents in General-Relativity and Quantum Gravity

Figure 4. Word cloud for Theoretical High Energy Physics documents

Figure 4. Word cloud for Theoretical High Energy Physics documents

Figure 5. Word cloud for Astrophysics

(Restricting the High Energy Physics category to only Theoretical papers caused this problem and the results were not very valuable, so I added additional subcategories to the HEP area including various topics in atomic physics and experimental HEP. This change is reflected in the results below.)

A Clustering Based Classifier

Given the small size of the training set, the random forest method described above worked reasonably well for the labeled data. However, as we shall see later, it was not very good at the unlabeled data from the popular press. So I tried one more experiment.

There are a variety of “unsupervised” classifiers based on clustering techniques. One of the standards is the K-means method. This method works by iterating over a space of points and dividing them into K subsets so that the members of each subset are closest to their “center” than they are to the center of any of the others clusters. Another is called Latent Sematic Indexing (LSI) and it is based on a singular value decomposition of the document-term matrix. And a third method is called Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) which build linear expressions of features that can be used to partition documents.

The way we use these three methods to build a trained classifier is a bit unconventional. The basic idea is as follows. Each of the three methods, K-means, LSI and LDA has a way to ask where a document fits in its clustering scheme. In the case of K-means this is just asking which cluster is nearest to the point represented by the document. We use the LSI and LDA implementations from the excellent gensim package. In the case of LSI and LDA, we can use a special index function which performs a similarity query.

As before we begin by converting documents into unit vectors in a very high dimension space. We begin with the list of documents.

The list of words from these abstracts is then filtered to remove Standard English stop words as well as a list of about 30 stop words that are common across all science articles and so are of no value for classification. This includes words like “data”, “information”, “journal”, “experiment”, “method”, “case” etc. Using the excellent pattern Python package from the Computational Linguistics & Psycholinguistics Research Center at the University of Antwerp, we extract all nouns and noun phrases as these are important in science. For example phrases like “black hole”, “abelian group”, “single cell”, “neural net”, “dark matter” has more meaning that “hole”, “group”, “cell”, “net” and “matter” alone. Including “bi-grams” like these is relatively standard practice in the document analysis literature.

For each document we build a list called “texts” in the code below. texts[i] is a list of all the words in the i-th document. From this we build a dictionary and then transform the Text list into another list called Corpus. Each element in Corpus is a list of the words in the corresponding document represented by their index in the dictionary. From this corpus we can build an instance of the LSI or LDA model. We next transform the corpus into tfidf format and then into the format LDA or LSI need. From these we create an index object that can be used to “look up” documents.

For example, suppose I have a new four-word document “dna genome evolution rna” and I want to find the abstracts in our collection that are most similar.

Document 534 is one with title “Recombinant transfer in the basic genome of E. coli” and is indeed a good match for our rather short query document.

The best of three classifier

So now we have three ways to find documents similar to any given document. Here is how we can use it to build a crude classifier we call “best-of-three”.

- Assume you have n target categories. At the top level we have n = five: Physics, Biology, CS, Math and Finance.

- Sort the training set of documents into n buckets where each bucket consist of those documents that correspond to one of the categories. So bucket 1 contains all training documents from physics and bucket 2 has all training documents from Biology, etc.

- Given a new document x we compute the top 5 (or so) best matches from each of the three methods (KM, LSI and LDA) as shown above. We now have 15 (or so) potential matches.

- We now have 15 (or so) potential matches. Unfortunately each of the three methods uses a different metric to judge them and we need to provide a single best choice. We take a very simple approach. We compute the cosine distance between the vector representing the document x and each of the 15 candidates. The closest document to x is the winner and we look to see in which bucket that document lives and the label of that bucket is our classification.

The Centroid classifier

Unit length vectors are points on a high dimensional sphere. The cosine distance between two vectors of unit length is simply the distance between those points. Because the best-of-three method uses the cosine distance as the final arbiter in a decision process we can envision an even simpler (and very dumb) method. Why not “summarize” each bucket of training set items with a single vector computed as the “centroid” of that set of training set documents. (By centroid here we mean the normalized sum of all the vectors in training set bucket k. ) We can then classify document x by simply asking which centroid is closest to x. This turns out to be a rather weak classifier. But we can improve it slightly using he best-of-three method. For each bucket k of documents with training label k, we can ask KM, LDA and LSI which other documents in the training set are close to those elements in k. Suppose we pick 5 of the nearby documents for each element of the bucket and add these to an extended bucket for label k as follows.

We now have buckets that are larger than the original and the buckets from different labels will overlap (have non-trivial intersections). Some physics documents may now also be in computer science and some math documents will now also be in biology, but this is not so bad. If it is labeled as being in physics, but it looks like computer science then let it be there too.

The Results

We now compare the methods RandomForest (rf), Best-of-Three (best) and the new centroid classifier (cent) against each other for all the labeled data. The results are complicated by two factors related to the selection of the training sets. The balance between the numbers of papers in each subcategory is not very good. At the top level, physics has thousands of papers and finance has only a few hundred. Similar imbalances exist in all of the individual disciplines. Consequently if you take a random selection of X% of the labeled data as the training set, then the prolific disciplines will be heavily represented compared to the small disciplines. The result is that the false positive rates for the heavy disciplines can be extremely high (greater than 10% of all documents.) On the other hand if you take a fixed number of papers from each discipline then the training set for the big disciplines will be very small. The compromise used here is that we take a fixed percent (75%) of the documents from each discipline up to a maximum number from each then we get a respectable balance, i.e. false positive rates below 10% . The table below is the result for the top level classification.

Table 4. Top-level results from 7107 labeled documents with a training set consisting of 63% (with a maximum of 1500 documents from each sub-discipline.)

Table 4. Top-level results from 7107 labeled documents with a training set consisting of 63% (with a maximum of 1500 documents from each sub-discipline.)

(In Table 4 and the following tables we have calculated the “correct” identifications as the percent of items of domain x correctly identified as being x. This is the same as “recall” in the ML literature. The “false pos” values is the percent of items incorrectly identified as being in category x. If n is the total number of documents and m is the number identified as physics but are not physics then the table represents 100*n/m in the physics column. This is not the same as the textbook definition of false positive rate. )

In the tables below we show the results for each of the disciplines using exactly the same algorithms (and code) to do the training and analysis.

Table 5. Physics sub-domain consisting of 3115 documents and a training set of 53%. (300 doc max per subcategory)

Table 5. Physics sub-domain consisting of 3115 documents and a training set of 53%. (300 doc max per subcategory)

Table 6. Math sub-domain consisting of 1561 documents and a training set size of 39% (200 doc max per subcategory)

Table 7. Biology sub-domain consisting of 1561 documents and a 39% training set size (200 docs max size per subcategory)

Table 8. Computer Science sub-domain consisting of 1367 documents and 56% training set size (200 doc max docs per subcategory)

Table 9. Finance sub-domain consisting of 414 documents and a 64% training set size (50 documents max per subcategory)

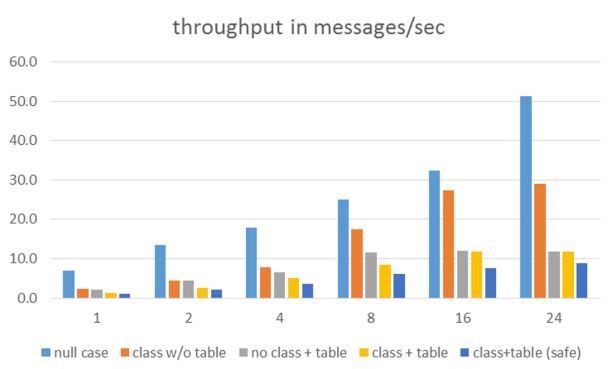

As can be seen from the numbers above that Random Forest continues to be the most accurate, but the Best-of-Three method is not bad and in some cases outperformed Random Forest. And, because we assume that science is very interdisciplinary, we can use both methods as a way to push documents through our system. In other words if bf and best agree that a document belong in category X, then we put it there. But if they disagree and one says category X and the other says category Y, then we put the document in both.

Non-labeled documents

Now we turn to the non-labeled data coming from the RSS feeds from Science Daily, Scientific American, New Scientist, Science Magazine and the New York Times. The reader may wonder why we bothered to describe the centroid method and list its performance in the table above when it is clearly inferior to the other methods on the labeled ArXiv data. The surprise is that it beats the Random Forest and Best-of-Three on the popular press data.

I do not have a good explanation for this result other than the fact that the popular press data is very different from the clean scientific writing in science abstracts. Furthermore the science press feeds are often very short. In fact they often look more like tweets. For example, one from Science Daily reads

“Scientists have found that graphene oxide’s inherent defects give rise to a surprising mechanical property caused by an unusual mechanochemical reaction.”

The subject here is materials science and the Best-of-Three algorithm came the closest and called this physics. In other cases all the algorithms failed. For example from the science day feed this article

“While advances in technology have made multigene testing, or \’panel testing,\’ for genetic mutations that increase the risk of breast or other cancers an option, authors of a review say larger studies are needed in order to provide reliable risk estimates for counseling these patients.”

was determined to be “Finance” by all three algorithms.

And there were many posts that had no identifiable scientific content. For example

“Casual relationships, bittersweet news about chocolate, artisanal lightbulbs and more (full text available to subscribers)”

or

“If social networks were countries, they’d be police states. To change that we may have to rebuild from the bottom up.

or

“Footsteps of gods, underground dragons or UFOs? Rachel Nuwer joins the fellowship of the rings out to solve the enigma in the grassy Namibian desert.”

This does not mean these stories had no scientific or educational value. It only means that the abstract extracted from the RSS feed was of no value in making a relevance decision.

Another major problem was that our scientific categories are way too narrow. A major fraction (perhaps 70%) of the popular press news feeds are about earth science, ecology, geophysics, medicine, psychology and general health science. For example, the following three have clear scientific content, but they do not match our categories.

“Consumption of sugary drinks increases risk factors for cardiovascular disease in a dose-dependent manner — the more you drink, the greater the risk. The study is the first to demonstrate such a direct, dose-dependent relationship.”

“Nearly a third of the world’s 37 largest aquifers are being drained faster than water can be returned to them, threatening regions that support two billion people, a recent study found.”

“While the risk of suicide by offenders in prison has been identified as a priority for action, understanding and preventing suicides among offenders after release has received far less attention.”

By extracting a random sample of 200 postings and removing those that either had no scientific content or no relationship to any of our main disciplines, the results were that Centroid was the best classifier of the remainder correctly identifying 56%. Best together with Centroid the success rate rose to 63%. Random forest only correctly identified 16% of the papers because it tended to identify many papers as mathematics if the abstract referred to relative quantities or had terms like “increased risk”.

Final Thoughts

The greatest weakness of the approaches I have outlined above is the fact that the methods do not provide a “confidence” metric for the selections being made. If the classifier has no confidence in its prediction, we may not want to consider the result to be of value. Rather than putting the document is the wrong category it can be better to simply say “I don’t know”. However it is possible to put a metric of “confidence” on Best and Centroid because each rank the final decisions based on the cosine “distance” (actually for the unit length vectors here, the cosine is really just the dot product of the two vectors). The nearer the dot product is to 1.0 the closer two vectors are.

For the Centroid method we are really selecting the classification category based on the closest topic centroid to the document vector. It turns out that for the majority of the public press documents the dot products with the centroids are all very near zero. In other words the document vector is nearly orthogonal to each of the topic centroids. This would suggest that we may have very little confidence in the classification of these document. If we simply label every document with a max dot product value less than 0.04 as “unclassifiable” we eliminate about 90% of the documents. This includes those documents with no clear scientific content and many of those that appear to be totally unrelated to our five theme areas. However, if we now compute the true positive rate of the centroid classifier on the remainder we get 80% correct. For Best or Centroid together we are now over 90% and RF is up to 35% (now slight above a random guess).

We can now ask the question what max dot product cutoff value will yield a true positive rate of 90% for the centroid method? The table below shows the true positive value and the fraction of the document collection that qualify for dot product values ranging from 0.04 to 0.15 (called the “confidence level” below.

Another way of saying this is that if the maximum of the dot products of the document vector with the topic centroids is above 0.05 the chance of a correct classification by the Centroid method is above 90%. Of course the downside is that the fraction of the popular press abstracts that meet this criteria is less than 7%.

Next Steps

The two great weaknesses of this little study are the small data set size and the narrowness of the classification topics. The total number of documents used to train the classifiers was very small (about 6,000). With 60,000 or 600,000 we expect we can do much better. To better classify the popular press articles we need topics like geoscience, ecology, climate modeling, psychology and public health. These topics make up at least 70% of the popular press articles. In a future version of this study we will include those topics.

Another approach worth considering in the future is an analysis based on the images of equations and diagrams. Scientists trained in a specialty can recognize classes of scientific equations such as those for fluid dynamics, electromagnetism, general relativity, quantum mechanics or chemical reaction diagrams or biochemical pathways, etc. These images are part of the language of science. Image recognition using deep neural networks would be an ideal way to address this classification problem.

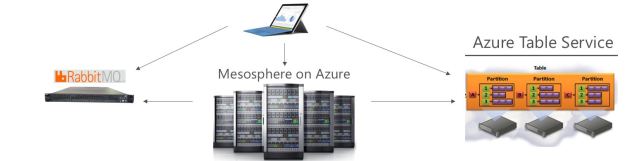

In the next post I will describe the implementation of the system as a network of microservices in the cloud. I will also release the code use here for the document training and I will release the data collection as soon as I find the best public place to store it.